Накба

| Накба | |

| |

| Ким названо | Constantin Zureiqd |

|---|---|

| Місце розташування | Підмандатна Палестина |

| Дата й час | 1948 |

| Персонаж твору | Farhad |

| Мета проєкту або місії | Єврейська державаd |

| Під впливом | Декларація Бальфура 1917 року, Розділ Османської імперії і План ООН по розділу Палестини |

| | |

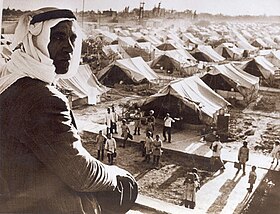

Накба (араб. النكبة, трансліт. an-Nakbah, дос. «лихо, катастрофа»),[2] також відома як Палестинська катастрофа, — це знищення палестинського народу й батьківщини в 1948 році та остаточне переміщення більшості палестинських арабів.[3][4] Термін використовується для опису як подій 1948 року, так і чинної окупації палестинців на Палестинських територіях (окупований Західний берег і Сектор Газа), а також їх переслідування й переміщення на палестинських територіях і в таборах палестинських біженців по всьому регіону.[5][6][7][8][9]

Основоположні події Накби відбулися під час і незабаром після Палестинської війни 1948 року на 78 % підмандатної Палестини, яка була оголошена Ізраїлем, вигнання та втеча 700 000 палестинців, пов'язане з цим зменшення населення та знищення понад 500 палестинських сіл сіоністськими ополченцями та наступне географічне стирання згадок про вигнанців, відмова палестинцям у праві на повернення, поява постійних палестинських біженців і «руйнування палестинського суспільства».[10][11][12][13] З тих пір деякі історики описують вигнання палестинців як етнічну чистку.[14][15][16]

У 1998 році Ясір Арафат запропонував, щоби палестинці відзначали 50-річчя Накби, проголосивши 15 травня, наступного дня після здобуття Ізраїлем незалежності в 1948 році, Днем Накби, формалізувавши дату, яка неофіційно використовувалася ще в 1949 році.[17][18]

Накба значно вплинула на палестинську культуру і є основоположним символом палестинської ідентичності разом із «хандалою», куфією та символічним ключем. Про Накбу написано незліченні книги, пісні та вірші.[19] Палестинський поет Махмуд Дервіш описав Накбу як «розширене сьогодення, яке триватиме в майбутньому».[20][21]

Складові частини[ред. | ред. код]

Накба охоплює вимушену міґрацію, позбавлення власності, відсутність громадянства й розкол палестинського суспільства.[3][4]

Вимушена міґрація[ред. | ред. код]

Упродовж Палестинської війни 1947—1949 рр. приблизно 700 000 палестинців утекли або були вигнані, що становило близько 80 % палестинських арабів, що мешкали на території, що стала Ізраїлем.[22][23] Майже половина цієї цифри (приблизно 250 000—300 000 палестинців) утекли або були вигнані напередодні Декларації незалежності Ізраїлю в травні 1948 року,[24] , який був названий казусом беллі для вторгнення Арабської ліги до країни, що призвело до арабо-ізраїльської війни 1948 року. У післявоєнний період велика кількість палестинців намагалися повернутися до своїх домівок; від 2700 до 5000 палестинців було вбито Ізраїлем протягом цього періоду, переважна більшість з них були беззбройними та мали намір повернутися з економічних чи соціальних причин.[25] Відтоді вигнання палестинців деякі історики називають етнічною чисткою.[14][15][16]

У той же час значна частина тих палестинців, які залишилися в Ізраїлі, стали внутрішньо переміщеними особами. У 1950 році UNRWA підрахувало, що 46 000 із 156 000 палестинців, які залишилися в межах кордонів, демаркованих як Ізраїль згідно з Угодами про перемир'я 1949 року, були внутрішньо переміщеними біженцями.[26][27] Сьогодні близько 274 000 арабських громадян Ізраїлю — або кожен четвертий в Ізраїлі — є внутрішньо переміщеними особами внаслідок подій 1948 року.[28]

Виселення й стирання пам'яті[ред. | ред. код]

План поділу ООН 1947 року передбачав 56 % території Палестини для майбутньої єврейської держави, тоді як палестинська більшість, 66 %, мала отримати 44 % території. 80 % землі в запланованій єврейській державі вже належало палестинцям, 11 % мали єврейський титул. До, під час і після війни 1947—1949 років сотні палестинських міст і сіл були обезлюднені й зруйновані.[29][30] Географічні назви по всій країні були стерті та замінені єврейськими назвами, іноді похідними від історичної палестинської номенклатури, а іноді новими винаходами. Численні неєврейські історичні об'єкти були знищені не лише під час воєн, а й упродовж кількох десятиліть. Наприклад, понад 80 % палестинських сільських мечетей було зруйновано, а артефакти вилучено з музеїв та архівів.

В Ізраїлі було прийнято низку законів для легалізації експропріації палестинських земель.[31][32]

Бездержавність і денаціоналізація[ред. | ред. код]

Обездержавлення палестинців є центральним компонентом Накби і продовжує бути характерною рисою палестинського національного життя до наших днів. Усі араби-палестинці відразу стали особами без громадянства в результаті Накби, хоча деякі прийняли інші національності. [33] Після 1948 року палестинці перестали бути просто палестинцями, натомість стали або ізраїльсько-палестинцями, палестинцями БАПОР, палестинцями Західного берега річки Йордан і палестинцями Гази, на додаток до ширшої палестинської діаспори, яка змогла отримати дозвіл на проживання за межами історичної Палестини і в таборах для біженців.[34]

Перший Ізраїльський закон про громадянство, прийнятий 14 липня 1952 року, денаціоналізував палестинців, зробивши колишнє палестинське громадянство «позбавленим суті», «незадовільним і невідповідним ситуації після створення Ізраїлю».[35][36]

Розкол суспільства[ред. | ред. код]

Накба стала першопричиною появи палестинської діаспори; в той же час, коли Ізраїль був створений як батьківщина для євреїв, палестинці були перетворені на «націю біженців» з «ідентичністю блукачів».[37] Сьогодні більшість із 13,7 мільйонів палестинців живуть у діаспорі, тобто за межами історичної території підмандатної Палестини, переважно в інших країнах арабського світу.[38] З 6,2 мільйона осіб, зареєстрованих спеціальним агентством ООН у справах палестинських біженців, UNRWA,[a] близько 40 % живуть на Західному березі річки Йордан і в Газі, а 60 % — у діаспорі. Велика кількість цих біженців з діаспори не інтегровані в приймаючі країни, про що свідчить постійна напруженість між палестинцями в Лівані або втеча палестинців з Кувейту в 1990-91 роках.[40]

Ці фактори призвели до формування палестинської ідентичності «страждання», у той час як детериторіалізація палестинців стала фактором об'єднання і координації у прагненні повернутися на втрачену батьківщину.[41]

Примітки[ред. | ред. код]

- ↑ Note: The 6.2 million is composed of 5.55 million registered refugees and 0.63m other registered people; UNRWA's definition of Other Registered Persons refer to "those who, at the time of original registration did not satisfy all of UNRWA's Palestine refugee criteria, but who were determined to have suffered significant loss and/or hardship for reasons related to the 1948 conflict in Palestine; they also include persons who belong to the families of other registered persons."[39]

- ↑ https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q3266633

- ↑ Honaida Ghanim (2009). Poetics of Disaster: Nationalism, gender, and social change among Palestinian poets in Israel after Nakba. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society. Т. 22. с. 23—39. JSTOR 40608203.

- ↑ а б (Webman, 2009)

- ↑ а б (Sa'di, 2002)

- ↑ Hanan Ashrawi, Address by Ms. Hanan Ashrawi [Архівовано 4 березня 2021 у Wayback Machine.], Durban (South Africa), 28 August 2001. World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Related Intolerances: "a nation in captivity held hostage to an ongoing Nakba, as the most intricate and pervasive expression of persistent colonialism, «apartheid, racism, and victimization» (original emphasis).

- ↑ Saeb Erekat, 15 May 2016, Haaretz, Israel Must Recognize Its Responsibility for the Nakba, the Palestinian Tragedy [Архівовано 26 лютого 2021 у Wayback Machine.], «The two-part makeup of the Nakba was borne through the destruction of Palestine and the construction of Israel. It encompasses around 350,000 internally displaced Palestinian citizens of Israel. It is seen through a racist legislative framework which legitimized the theft of Palestinian refugee land as enumerated in the Absentee Property Law… For Palestinians worldwide, the Nakba was not merely a day in history 68 years ago, but an entire system of daily forced subjugation and dispossession culminating in today's Apartheid regime.»

- ↑ (Sa'di та Abu-Lughod, 2007, с. 10)

- ↑ (Manna', 2013, с. 87)

- ↑ Bashir та Goldberg, 2018, с. 33, footnote 4: "In Palestinian writings the signifier “Nakba" came to designate two central meanings, which will be used in this volume interchangeably: (1) the 1948 disaster and (2) the ongoing occupation and colonization of Palestine that reached its peak in the catastrophe of 1948"

- ↑ Masalha, 2012, с. 3.

- ↑ Dajani, 2005, с. 42: "The nakba is the experience that has perhaps most defined Palestinian history. For the Palestinian, it is not merely a political event — the establishment of the state of Israel on 78 percent of the territory of the Palestine Mandate, or even, primarily a humanitarian one — the creation of the modern world's most enduring refugee problem. The nakba is of existential significance to Palestinians, representing both the shattering of the Palestinian community in Palestine and the consolidation of a shared national consciousness."

- ↑ Sa'di та Abu-Lughod, 2007, с. 3: "For Palestinians, the 1948 War led indeed to a "catastrophe." A society disintegrated, a people dispersed, and a complex and historically changing but taken for granted communal life was ended violently. The Nakba has thus become, both in Palestinian memory and history, the demarcation line between two qualitatively opposing periods. After 1948, the lives of the Palestinians at the individual, community, and national level were dramatically and irreversibly changed."

- ↑ Khalidi, Rashid I. (1992). Observations on the Right of Return. Journal of Palestine Studies. 21 (2): 29—40. doi:10.2307/2537217. JSTOR 2537217.

Only by understanding the centrality of the catastrophe of politicide and expulsion that befell the Palestinian people – al-nakba in Arabic – is it possible to understand the Palestinians' sense of the right of return

- ↑ а б Ian Black (26 листопада 2010). Memories and maps keep alive Palestinian hopes of return. The Guardian.

- ↑ а б Ilan Pappé, 2006

- ↑ а б Shavit, Ari. «Survival of the Fittest? An Interview with Benny Morris» [Архівовано 2021-09-05 у Wayback Machine.]. Logos. Winter 2004

- ↑ Schmemann, Serge (15 травня 1998). MIDEAST TURMOIL: THE OVERVIEW; 9 Palestinians Die in Protests Marking Israel's Anniversary. The New York Times. Архів оригіналу за 5 березня 2022. Процитовано 7 квітня 2021.

We are not asking for a lot. We are not asking for the moon. We are asking to close the chapter of nakba once and for all, for the refugees to return and to build an independent Palestinian state on our land, our land, our land, just like other peoples. We want to celebrate in our capital, holy Jerusalem, holy Jerusalem, holy Jerusalem.

- ↑ Gladstone, Rick (15 травня 2021). An annual day of Palestinian grievance comes amid the upheaval. The New York Times. Архів оригіналу за 15 травня 2021. Процитовано 15 травня 2021.

- ↑ Masalha, 2012, с. 11.

- ↑ Darwish, 2001.

- ↑ Williams, 2009, с. 89.

- ↑ Masalha, Nur (1992). Expulsion of the Palestinians. Institute for Palestine Studies, this edition 2001, p. 175.

- ↑ Rashid Khalidi (September 1998). Palestinian identity: the construction of modern national consciousness. Columbia University Press. с. 21. ISBN 978-0-231-10515-6. Архів оригіналу за 14 січня 2023. Процитовано 27 квітня 2021.

In 1948 half of Palestine's ... Arabs were uprooted from their homes and became refugees

- ↑ According to Morris's estimates, 250,000 to 300,000 Palestinians left Israel during this stage, whereas Keesing's Contemporary Archives in London place the total number of refugees before Israel's independence at 300,000, as quoted in Mark Tessler's A History of the Arab–Israeli Conflict: «Keesing's Contemporary Archives» (London: Keesing's Publications, 1948—1973). p. 10101.

- ↑ Benny Morris (1997). Israel's Border Wars, 1949–1956: Arab Infiltration, Israeli Retaliation, and the Countdown to the Suez War. Clarendon Press. с. 432. ISBN 978-0-19-829262-3.

The available documentation suggests that Israeli security forces and civilian guards, and their mines and booby-traps, killed somewhere between 2,700 and 5,000 Arab infiltrators during 1949–56. The evidence suggests that the vast majority of those killed were unarmed. The overwhelming majority had infiltrated for economic or social reasons. The majority of the infiltrators killed died during 1949–51; there was a drop to some 300–500 a year in 1952–4. Available statistics indicate a further drop in fatalities during 1955–6, despite the relative increase in terrorist infiltration.

- ↑ Number of Palestinians (In the Palestinian Territories Occupied in 1948) for Selected Years, End Year. Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Архів оригіналу за 6 березня 2021. Процитовано 27 квітня 2021.

- ↑ עיצוב יחסי יהודים - ערבים בעשור הראשון. lib.cet.ac.il. Архів оригіналу за 8 жовтня 2022. Процитовано 8 жовтня 2022.

- ↑ Nihad Bokae'e (February 2003). Palestinian Internally Displaced Persons inside Israel: Challenging the Solid Structures (PDF). Badil Resource Centre for Palestinian Refugee and Residency Rights. Архів (PDF) оригіналу за 7 квітня 2016. Процитовано 15 квітня 2017.

- ↑ Morris, Benny (2003). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00967-7, p. 604.

- ↑ Khalidi, Walid (Ed.) (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- ↑ Forman G, Kedar A (Sandy). From Arab Land to ‘Israel Lands’: The Legal Dispossession of the Palestinians Displaced by Israel in the Wake of 1948. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space. 2004;22(6):809–830. doi:10.1068/d402

- ↑ Kedar A (Sandy), The Legal Transformation of Ethnic Geography: Israeli Law and the Palestinian Landholder 1948—1967, 33 N.Y.U. J. Int'l L. & Pol. 923 (2000—2001)

- ↑ Sa'di та Abu-Lughod, 2007, с. 136.

- ↑ Butenschon, N. A.; Davis, U.; Hassassian, M. (eds.). «Citizenship and the State in the Middle East: Approaches and Applications» (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2000), p. 204.

- ↑ Lauterpacht, H. (ed.). «International Law Reports 1950» (London: Butterworth & Co., 1956), p.111

- ↑ Kattan, V. (2005). «The Nationality of Denationalized Palestinians». Nordic Journal of International Law 74(1), 67–102. DOI:10.1163/1571810054301004

- ↑ Schulz, 2003, с. 1–2: "One of the grim paradoxes of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is that the foundation of the state of Israel, intended to create a safe haven for the 'archetypical' Jewish diaspora, spelt the immediate diasporisation of the Arab Palestinians. The territorialisation of the Jewish diaspora spurred a new 'wandering identity' and the Palestinians became a 'refugee nation'. To the Palestinians, the birth of Israel is thus remembered as the catastrophe, al-nakba, to imprint the suffering caused by dispersal, exile, alienation and denial ... The nakba is the root cause of the Palestinian diaspora."

- ↑ Schulz, 2003, с. 1–3.

- ↑ UNRWA Annual Operational Report 2019 (PDF). Архів (PDF) оригіналу за 13 березня 2021. Процитовано 7 квітня 2021.

- ↑ Schulz, 2003, с. 2: "Although the PLO has officially continued to demand fulfilment of UN resolution 194 and a return to homes lost and compensation, there is not substantial international support for such a solution. Yet it is around the hope of return that millions of Palestinian refugees have formed their lives. This hope has historically been nurtured by PLO politics and its tireless repetition of the 'right of return'—a mantra in PLO discourse. In addition, for hundreds of thousands (or even millions) of Palestinian refugees, there are no prospects (or desires) for integration into host societies. In Lebanon, the Palestinians have been regarded as 'human garbage' (Nasrallah 1997), indeed as 'matters out of place' (cf. Douglas 1976), and as unwanted."

- ↑ Schulz, 2003, с. 2–3: "Fragmentation, loss of homeland and denial have prompted an identity of ’suffering', an identification created by the anxieties and injustices happening to the Palestinians because of external forces. In this process, a homeland discourse, a process of remembering what has been lost, is an important component ... Therefore the dispersal (shatat in Arabic) and fragmentation of the Arab population of Palestine have served as uniting factors behind a modern Palestinian national identity, illuminating the facet of absence of territory as a weighty component in creations and recreations of ethnic and national identities in exile. Deterritorialised communities seek their identity in the territory, the Homeland Lost, which they can only see from a distance, if at all. The focal point of identity and politics is a place lost."

Джерела[ред. | ред. код]

- Alon, Shir (2019). No One to See Here: Genres of Neutralization and the Ongoing Nakba. Arab Studies Journal. Georgetown University. 27 (1): 91—117. Архів оригіналу за 14 січня 2023. Процитовано 22 грудня 2022.

- Vescovi, Thomas (15 січня 2015). La mémoire de la Nakba en Israël: Le regard de la société israélienne sur la tragédie palestinienne. Editions L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-336-36805-4. Архів оригіналу за 14 січня 2023. Процитовано 2 квітня 2021.

- Baumgarten, Helga (2005). The Three Faces/Phases of Palestinian Nationalism, 1948–2005. Journal of Palestine Studies. 34 (4): 25—48. doi:10.1525/jps.2005.34.4.25. JSTOR 10.1525/jps.2005.34.4.25.

- Zureiq, Constantin (1956). The Meaning of the Disaster. Khayat's College Book Cooperative. Архів оригіналу за 14 січня 2023. Процитовано 2 квітня 2021. (Original Arabic version: Zureiq, Constantin (1948). وصف الكتاب. دار العلم للملايين.)

- Sa'di, Ahmad H.; Abu-Lughod, Lila (2007). Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the Claims of Memory. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13579-5.

- Nashef, Hania A.M. (30 жовтня 2018). Palestinian Culture and the Nakba: Bearing Witness. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-38749-1. Архів оригіналу за 14 січня 2023. Процитовано 2 квітня 2021.

- Masalha, Nur (9 серпня 2012). The Palestine Nakba: Decolonising History, Narrating the Subaltern, Reclaiming Memory. Zed Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84813-973-2. Архів оригіналу за 14 січня 2023. Процитовано 2 квітня 2021.

- Bashir, Bashir; Goldberg, Amos (13 листопада 2018). The Holocaust and the Nakba: A New Grammar of Trauma and History. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54448-1. Архів оригіналу за 14 січня 2023. Процитовано 2 квітня 2021.

- Wermenbol, Grace (31 травня 2021). A Tale of Two Narratives: The Holocaust, the Nakba, and the Israeli-Palestinian Battle of Memories. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-84028-6. Архів оригіналу за 14 січня 2023. Процитовано 2 квітня 2021.

- Caplan, Neil (2012). Victimhood in Israeli and Palestinian National Narratives. Bustan: The Middle East Book Review. 3 (1): 1—19. doi:10.1163/187853012x633508. JSTOR 10.1163/187853012x633508.

- Khoury, Nadim (January 2020). Postnational memory: Narrating the Holocaust and the Nakba. Philosophy & Social Criticism. 46 (1): 91—110. doi:10.1177/0191453719839448. S2CID 150483968.

- Sa'di, Ahmad H. (2002). Catastrophe, Memory and Identity: Al-Nakbah as a Component of Palestinian Identity. Israel Studies. 7 (2): 175—198. doi:10.2979/ISR.2002.7.2.175. JSTOR 30245590. S2CID 144811289.

- Manna', Adel (2013). The Palestinian Nakba and Its Continuous Repercussions. Israel Studies. 18 (2): 86—99. doi:10.2979/israelstudies.18.2.86. JSTOR 10.2979/israelstudies.18.2.86. S2CID 143785830.

- KOLDAS, UMUT (2011). The 'Nakba' in Palestinian Memory in Israel. Middle Eastern Studies. 47 (6): 947—959. doi:10.1080/00263206.2011.619354. JSTOR 23054253. S2CID 143778915.

- Sayigh, Rosemary (1 листопада 2013). On the Exclusion of the Palestinian Nakba from the 'Trauma Genre'. Journal of Palestine Studies. 43 (1): 51—60. doi:10.1525/jps.2013.43.1.51. JSTOR 10.1525/jps.2013.43.1.51.

- Lentin, Ronit (19 липня 2013). Co-memory and melancholia: Israelis memorialising the Palestinian Nakba. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1-84779-768-1. Архів оригіналу за 14 січня 2023. Процитовано 2 квітня 2021.

- Al-Hardan, Anaheed (5 квітня 2016). Palestinians in Syria: Nakba Memories of Shattered Communities. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54122-0. Архів оригіналу за 14 січня 2023. Процитовано 2 квітня 2021.

- Dajani, Omar (2005). Surviving Opportunities. У Tamara Wittes Cofman (ред.). How Israelis and Palestinians Negotiate: A Cross-cultural Analysis of the Oslo Peace Process. US Institute of Peace Press. ISBN 978-1-929223-64-0. Архів оригіналу за 14 січня 2023. Процитовано 2 квітня 2021.

- Webman, Esther (25 травня 2009). The Evolution of a Founding Myth: The Nakba and Its Fluctuating Meaning. У Meir Litvak (ред.). Palestinian Collective Memory and National Identity. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-62163-3. Архів оригіналу за 14 січня 2023. Процитовано 2 квітня 2021.

- Schulz, Helena Lindholm (2003). The Palestinian Diaspora: Formation of Identities and Politics of Homeland. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26821-9. Архів оригіналу за 14 січня 2023. Процитовано 7 квітня 2021.

- Masalha, Nur (2008). Remembering the Palestinian Nakba: Commemoration, Oral History and Narratives of Memory (PDF). Holy Land Studies. 7 (2): 123—156. doi:10.3366/E147494750800019X. S2CID 159471053. Шаблон:Project MUSE. Архів (PDF) оригіналу за 3 червня 2022. Процитовано 30 квітня 2022.

- Darwish, Mahmoud (10-16 May 2001). Not to begin at the end. Al-Ahram Weekly. № 533. Архів оригіналу за 2 грудня 2001.

- Williams, Patrick (2009). ‘Naturally, I reject the term "diaspora"’: Said and Palestinian Dispossession. У M. Keown, D. Murphy and J. Procter (ред.). Comparing Postcolonial Diasporas. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-0-230-23278-5. Архів оригіналу за 14 січня 2023. Процитовано 23 квітня 2021.

|